surfresearch.com.au

mccoy : design, 1981.

mccoy : design, 1981.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

surfresearch.com.au

mccoy : design, 1981. |

| Geoff

McCoy: Design |

Mitchell

Rae: Tails |

Phil

Byrne: Clinker Bottoms |

Col Smith: Conaves |

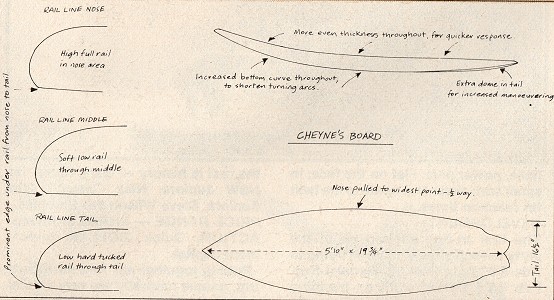

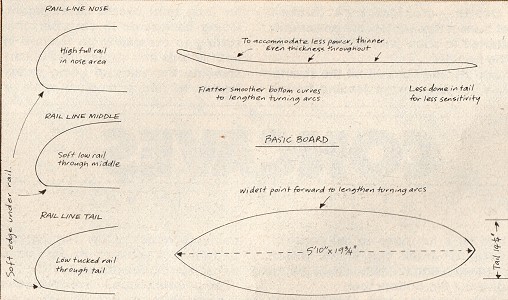

| The best way for me

to explain what we are doing is to give you two

examples of our range. I will explain the various functions of each extreme and naturally in between takes care of itself. The basic board: This term applies to a clean outline board, smooth bottom — in other words no real prominent reaction points to give the board definite performance advantages and disadvantages. This design is for smooth all-round performance. Usually surfboards react as they look, smooth soft lines and curves give smooth soft even performance. As the board takes on more prominent design features, it gives a quicker, harsher reaction. What I am saying is, the relationship between the board's capabilities and the surfer's ability is very important. It's to no one's advantage if your ability is for a 'Porsche' and you are trying to ride a 'Formula One Turbo'. The majority of surfers these days are riding boards that are over designed for them. They have too high a performance level for the surfers' abilities. This applies to a very high percentage of designs available right now. It's OK to cut away the outline of the board, gouge out grooves in the bottom and put lumps and bumps generally throughout the board. The only trouble is they all change the performance of the board to varying degrees. An important thing to remember is that as boards decrease in size — not only length, but plan shape area and thickness — they are become lighter. Definitely not stronger though. Keeping this in mind you could imagine taking two identical surfboards, except for the actual weight of the boards — one is one pound lighter than the other. The lighter board will have a quicker reaction time than the heavy board — it's obvious. The board would even have a natural flotation point higher than the heavy board, less displacement... more manoeuvrability. |

|

| Because I am

putting more curve in the bottom (length and width),

it is increasingly more difficult to flow all the

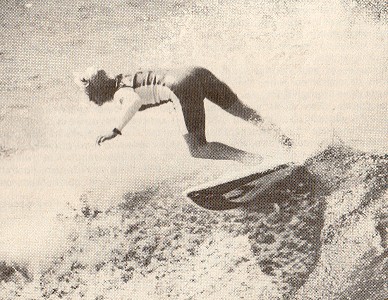

curves together. So, for now at least, Cheyne's board has prominent design features that as I mentioned before give it more obvious performance characteristics, making it harder to ride but more capable of higher performance levels. It's like the 'Porsche' and the 'Formula One Turbo'. The Porsche is a refined version of a race car, or a high performance road car. It has had ail the corners rounded out to cater for the less skilled driver. Our basic board has been designed with the same appeal. The Formula One Turbo is a full brute race car. Hard to tune, difficult to control, but in the right hands it is capable of awesome performance levels. Cheyne's board is in the same performance bracket. Both boards I have described perform the functions that are asked of them... it's vital that the surfer chooses the right one! Geoff McCoy Photo Peter Simons

|

|

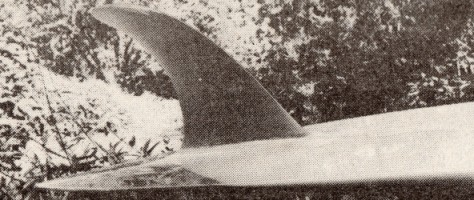

| From the early

seventies, this design has been refined and tested

in search of speed and manoeuvrability, namely,

control in a versatile surfboard. It favours the juice, but can function in the slop, and a great deal of variation can be employed within the design to accommodate the needs of various surfers and waves. The original concave design in 1970 came from Glynn Ritchie, David Chidgey and myself. The chines were added later as a safety factor and to reduce rail catch. The tucked-in nose and the flexible tail were introduced in about 1975. The flex, of course, inspired by George Greenough. Basically the design employs an even curve planshape, widest point slightly forward of centre, and a variety of tailshapes (I favour pintails and roundtails). |

|

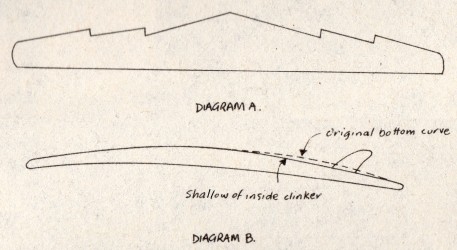

| Across the bottom

are a series ot straight planing edges that move

outwards from the boat's centre as an exaggerated

Vee, overlapping each other (diagram A). The number of Vs depends on the number of clinkers, the clinkers being formed by laying one plank over another. With surfboards, this effect is shaped into the foam (a nightmare for the production team in construction of these boards). The main distinctive feature is that there are no curved areas but all straights. The bottom is designed to reduce sideway slide — the edges of the clinkers give the bottom of the board more bite into the wave face. By doing this the board is converting energy lost by sideway drift into forward thrust. Because of this first basic function, the bottom design is particularly well suited to twin fins. |

|

|

Tracks May 1981 Number 128. Australian Unorthodox : The Religion of Oz Design Dougal Walker : The Tri-Fin - Did God Mean It To Be? Terry Fiztgerald : Drifta III Rod Hocker : Conaves and Fin Boxes. Geoff McCoy: Design Mitchell Rae: Tails

Phil Byrne: Clinker Bottoms Col Smith: Conaves |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|