surfresearch.com.au

mctavish, shaw & berry : mals, mats & kneelos, 1977.

mctavish, shaw & berry : mals, mats & kneelos, 1977.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

surfresearch.com.au

mctavish, shaw & berry : mals, mats & kneelos, 1977. |

| Bob

McTavish : Modern Malibu |

Dave

Shaw : Surf Mats |

Peter

Berry : Knee-boards |

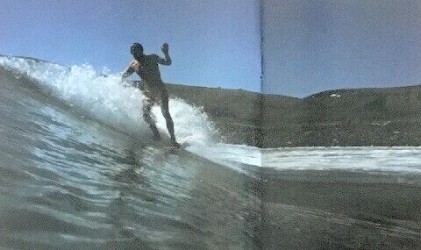

| When we put

the small board together we had a principle

in mind - to combine the speed area in the

turning area. This meant you could keep the power through your turn, resulting in today's arcing power surfing. OK. This is just fine when there is enough room to carve - size wise head high or over, surface smooth. But what about the all-too-common small days, sloppy days, just plain junk days. And those perfect peeling point mini-days. Re-enter the big board. With its many square feel of soft planing area it glides over dead spots, connects the power pockets and develops phenomenal speed from small weak waves. That's the starting point. McTavish nose trimming

onto the green.

###

|

|

| The other day

at the point I dropped in on a guy on a

small board. I didn't think he had a chance. The wave was about six feet. I trimmed my big board for all it was worth, then added a stretch five. It really threw over and I was right in there for a couple of seconds. Then the guy on the small board appeared below me. We both got bombed. I felt lousy. He came up hooting! Is the big board faster? ###

It's a case

of float or fly.When you need to float, the big board is faster, when there is the power to fly, the small board is faster. ###

|

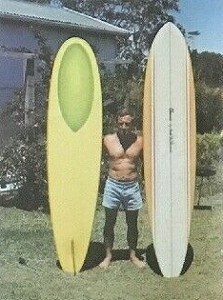

Little Mac and his big fun boards. |

Surfer Magazine - "Wide boards (21" and over) give more glide and stability Compare them to birds that soar, eg pelicans and eagles. The pelican can coast on the slightest updraught from the smallest wave, while the seagulls who have narrow wings, can't glide until the surf is larger. It's the same for wide vs. narrow boards. Average surf ridden calls for wider boards." - Skip Frye Fair enough? ###

Midget called it high speed stall and low speed stall after hang-gliding awhile — Hang gliding hanging on the nose and gliding under section alter section. A nice way to spend a windy afternoon - |

McTavish contolling the situation from the tip. |

|

Mat Mechanics

A Comprehensive Composition by Canvas Commando Dave Shaw. Let's face it, mat riding will never reach the mass appeal equal to that of surfboard riding. The machinery is just not sleek enough, nor is it the totally responsive go-anywhere-on-a-wave vehicle, but more "blob-like". However, fun is fun and riding rubber ducks is certainly that. While fun is important, a positive attitude towards manoeuvres will make rhe excursion into mat riding a very satisfying pastime, certainly equal to other forms of self-expression. Mat riding does take a certain amount of dull and not everyone can get the hang of it. Some of my friends who are quite good surfboard riders have claimed that they have found if difficult and not easy to pick up. |

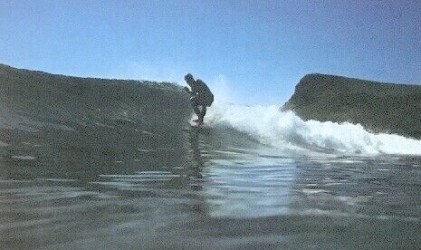

Dave Shaw testing theories

for this story. Photo: Core.

|

|

Photo: Shaw. Photo: Core.

|

|

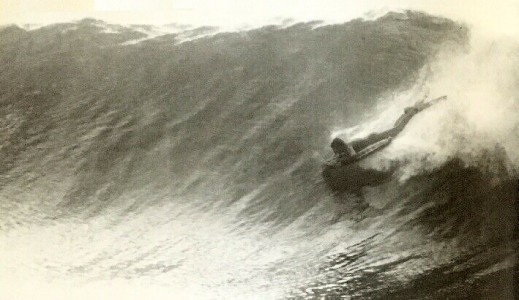

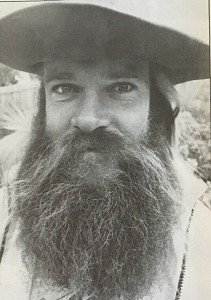

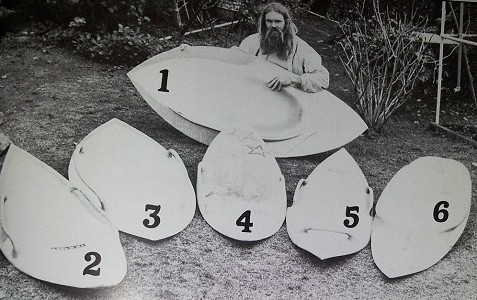

Who is this man & why are his kneeboards so radical? |

Page 43 Design : Peter Berry

Story and photos by Chris Elfes A young South Australian kneeboarder by the name of Paul Mlinards is quickly opening a package at an Adelaide Airport freight terminal. After tearing the package apart and revealing me contents, Paul suddenly goes off the deep end and starts ranting and raving, much to the bewilderment of some startled airline employees, who are staring in almost disbelief at the young surfer. What they didn't know was that Paul's package contained a new kneeboard, built for hlm by Peter Berry and you see, well, Peter Berry just happens to design and build the most radical and imaginative kneeboards yet conceived. Peter Berry comes from the Maroubra area on Sydney's southern beaches and builds his far out kneeboards under the label of Nomad. If you take a good long look at these photos of his equipment, you'll probably understand why Paul Minards was so surprised when he opened his package and found one of these radical irnie machines inside. |

|

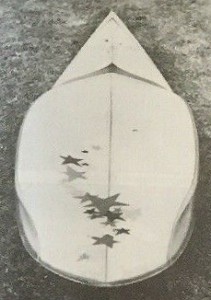

Unique double

rail, eliminates handles. |

The man and his machine. |

Neil Cameron, attempting a 360. |

| No. 1 Dimensions: 5'7" x 26 1/2'' Built: September Design: Step bottom, full pintail with double rails. The rails are flexible for three-quarters the length of the board. Comment: Works well in long walled waves sized three to eight foot. It can ride a long way out from the curl and can do full rail cutbacks without the fin in the water. No. 3 Dimensions: 5'8" x 25" Built: August 1976. Design: Pin nose and tail with slight vee under nose and tail. Comment: A very loose board has the ability to hold in well in steep and critical sections. Will handle anything from three to 10 feet. No. 4 Dimensions: 6'3" x 21" Built: December 1970 Design: Pintail with slight vee in the tail. The first board I ever constructed with handles. Comment: A very versatile board that works well in all sorts of waves. It has been ridden successfully in everything from three to 15 feet. No. 5 Dimensions: 7'2" x 21 1/2'' Built: July 1973 Design: Has a step in the rail line, similar to a Stinger. It has a vee in the nose and tail. The bottom has two heavy concaves that form an air cushion. It has a two foot long Keel fin. Comment: It's a hard board to turn, but once it gets going it makes light work of heavy waves. |

No. 2 Dimensions: 5'9" x 21 1/4" Built: August 1974 Design: Heavy double concave with kicked down narrow pintail. Comment: Works well in very fast waves. At high speeds it becomes highly manoeuvrable. Sits high in the lip.  No. 6 Dimensions: 6 0 x 20 1/2'' Built: (Not supplied) Design: Round tail with vee running the entire length of the board. It has double rails instead of conventional handles. Comment: Works best at high speed, not a slop riding board. |

Merrin

Surfmats

|

Peter

Townend : G&S Surfboards

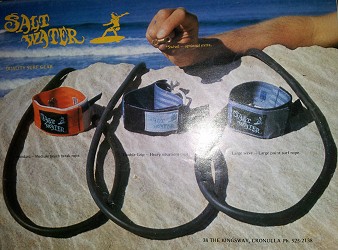

Saltwater

Legropes

|

Terry

Richardson: G&S Surfboards

|

|

|

|

|

|

|