surfresearch.com.au

silk with van dyke : surfing the north shore, 1963

silk with van dyke : surfing the north shore, 1963

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

surfresearch.com.au

silk with van dyke : surfing the north shore, 1963 |

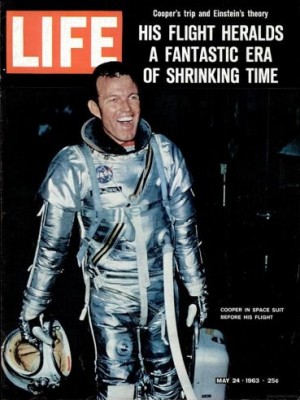

| Life

Time-Life Publishers, USA. 24 May 1963. |

Life

International Time Life, (Melbourne). Volume 34 Number 10, 3 June 1963. |

| Surfing in California, 7 February 1938. | California Surfing, 26 August 1940. | Aquatic Adventure Down Under, 15 September 1958. | Riding the Wild Waves, 24 May 1963. |

| Dick Dale, King of "Surfing Music", August 30, 1963. | Skateboards, June 5, 1964. | Joyce Hoffman-surfing champ, 14 October 1966. | (Surfing Photos), 20 March 1967. |

| Murf the Surf, and jewel robbery, 21 April 1967. | The Peril of the Surf, March? 1968. | Big Surf- Surf pool in Arizona, 6 March 1970. |

|

Page 56

Elite surfer's peril and ecstasy

in Hawaii

Riding the Wild Waves

When waves kindled by some faraway storm reach the awesome height of 30 feet off Oahu's northern beaches most men gasp and stare. But a very small, courageous band of surfers, mostly expatriates from California and Australia, get on their boards and risk their lives on the mountainous crests of foaming fury in a sport every bit as exhilarating - and nearly as dangerous - as skiing over Niagara on a barrel stave. The men who ride the big ones in Hawaii actually ski down the shoulder of a wave away from the curl (at fold on opposite page). [pages 58-59] They call the first breathtaking schuss "taking the drop." Their boards accelerate up to 35 mph so rapidly that they kick up wakes like speedboats. And a merciless mauling awaits the unfortunate who doesn't complete his ride. He is driven downward by the appalling maelstrom, tossed around, sucked back down and frequently, after fighting up for a desperate gulp of air, hammered down again by the next wave. The astonishing photographs on these pages capture the peril and ecstasy of surfing's elite corps. Its membership numbers less than 100, and three of them were killed riding the wild waves last year. Photographed

for LIFE by GEORGE SILK

|

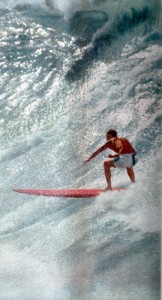

Page 57

At Sunset Beach, with

offshore breeze feathering foam

and rainbow hanging above him, surfer does a right-hand slide on a thundering 15-footer. |

|

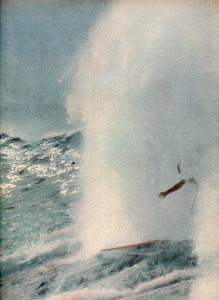

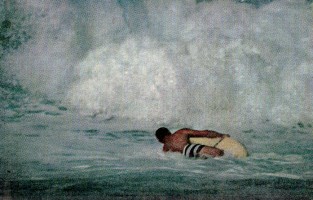

Page 58 [Fold-Out Sequence]

Explosion

of Water for the Unwary

The slightest miscue in timing can cause a

dunking.

Here Rick Grigg gets on 20-footer too late (above/right)and fails to pick up enough speed to avoid its menacing crest (right). ]

|

|

|

|

Page 59 |

|

Page

60

|

Page 61

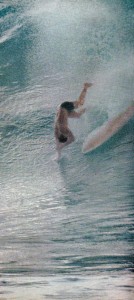

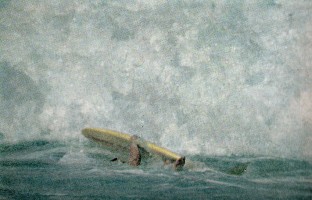

Free Falls, High Dives, Dangerous

Dunkings

In wild surf with waves breaking irregularly, Rick Grigg bails out (left) at Banzai Beach. He dives clear of board which becomes a menace when loose in the turbulence. Grigg was not hit but had other trouble: "I almost drowned," he said. Jose Angel of Hawaii has a perilous moment when he is almost

skewered by his board (right) after

free-falling down the face of a 22-foot wave. Being hit by

a board is the most common cause

of injury or death in big-wave surfing. Joe Kaohi

maneuvers desperately to cling to

board.

At Banzai Beach waves curl so evenly that they leave an air space called a "Banzai pipe" just under the crest. Getting a ride in this tunnel is considered the ultimate in surfing thrills. |

|

| Pages 62-63

Boring

from Below

Before riding in on

great waves men must sometimes first fight their

way out through

foaming barriers like the one above. This surfer was repulsed twice before he finally gave up. Best way through the huge combers is under them. At right (below) Greg Noll shows the technique.

He lies on board in first picture, rolls over as wave approaches (center), then clutches board tightly and prepares to duck under it. |

|

|

|

Pages 64-65 |

Burst of Speed to Catch a Ride

Once out beyond the booming rows

of breakers, surfers enter an unreal world."It's clean and beautiful," one of them explains, "like you've never been there before." They talk to the water as they prowl around searching for just the right wave. The surfer at left, Preston Leavey, has finished his talking and is now paddling frantically to get on a wave and begin his ride. The fierce exultation of the moment is magnified by the camera, which is bolted to the front of the board and has recorded the glitter of refracted light from flying spray and drops of water on the camera housing. Until the late 1940s no one dared expose himself in this fashion to the great waves on Oahu's north shore. Hawaii's ancient chieftains used to coast regally in on small waves before their admiring subjects on great loglike boards which weighed 160 pounds, but they dared not defy the big waves. What changed this slow regal ride into today's death-defying sport was development of a lightweight, highly maneuverable board of balsa wood. Two young surfers named Woody Brown and Dick Cross used the light boards to pioneer the big waves. The body of Cross was never found after he disappeared into a ferocious 40-footer in 1943. |

| Page 66-67

Nick Beck of

Honolulu gets up enough speed on his light

board to become synchronized with a wave and

assumes a balanced crouch.

At this point, while doing about 20 mph, he took his own picture by activating a camera on the front of his board with string wrapped around his left hand. At the very top of the wave, where Beck now hovers, most big-wave surfers are assailed by grave apprehensions. "Sometimes you want to stop," confesses Rick Grigg, "but there's a very forceful drive inside you that says, 'I've gone this far; I can't stop.' If you hesitate for just a moment, if you don't maintain confidence, you'll lean back and get wiped out"-i.e., dumped into the boiling surf. The take-off is the most critical part of big-wave riding. "Once you hit the take-off and get the board trimmed and sliding," says Buzzy Trent, another expert surfer, "you have the wave 90% conquered." From there to the end of the ride it's sheer, breathless joy. The path is diagonally away from the wave's foaming crest. Contrary to general opinion no one ever rides a big wave straight in. It just can't be done. |

Tense Poise at the

Peak

|

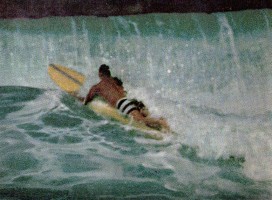

Pages 68-69 Out of

This World

|

A pair of riders, cutting

frothy furrows in the wall of a wild 18-footer,

seem headed on a collision course at Sunset Beach. At times like this they scream, "Let me in! Let me in!" But rarely do they hear each other above the awful thunder behind them. "You hear a sharp crack, and then you have the rumble of the soup rushing toward the beach," says Buzzy Trent in the lingo of the surfing fraternity. "The crack comes from the hollow under the crest . . . when the wave collapses on itself the air trapped inside explodes outward like a rifle shot, or a crack of thunder." Sometimes the uproar includes the crack of a board itself, for the forces unleashed when a big wave explodes can splinter a board or propel it skyward from the depths like a Polaris missile. Most drownings occur when an upended surfer is knocked unconscious by his board. "I would like to see a breakthrough in the development of a good safety helmet," says veteran Buzzy Trent. But he admits that it might be hard to get the daredevil surfers to wear them. "You see how these guys are. I probably wouldn't wear one myself." |

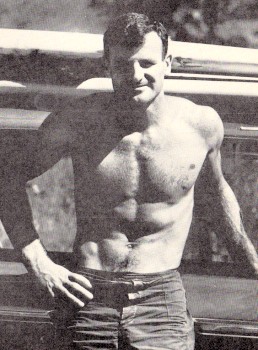

| Page 73

Pure

Pleasure of Being Half Killed

by

GEORGE SILK

Surf and sun have burned his skin to a permanent bronze, and when he moves, his muscles ripple like a boxer's. To keep fit, which he says is vital to survive in this sport, he swims a mile several times a week and runs a mile every other day on the beach. To condition self for the fight with rip tides and undertow, he ties a piece of rope around his waist and anchors it to the side of a swimming pool. Against this resistance, he swims a; hard as he can for 10 minutes. To get used to underwater pressure 40 feet down, which can hit him after being dumped by a big wave, he skindives to that depth. All this conditioning paid off one day six years ago while he was riding 25-foot waves at Haleiwa. "A big one drove me down into complete darkness," he told me, shrugging his shoulders as if to shake off the memory. "I struggled for the surface, but crashed into the coral bottom—I was swimming the wrong way. I was so upset I threw up and then blacked out. The next thing I knew, I was on the surface. But as I gulped for air, another wave hit me. If I hadn't succeeded in getting to the shoulder of the third wave, I'm sure I would have drowned. . . . "Many of us ride to supplement something lacking in our lives," he said, leaning against a car in Haleiwa heaped with surfboards. |

CONTINUED

|

|

Life

International Time Life, Melbourne. 3 June 1963 Volume 34 Number 10 Cover: The Wildest Water Sport: Surf Riding in Hawaii. Life (US edition) 24 May 1963. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|