robert rattray : padua, lake botsumtwi, africa, 1921

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

surfresearch.com.au

robert rattray : padua, lake botsumtwi, africa, 1921 |

The padua

of Lake Botsumtwi is a remarkable instance of an ancient

design of water-caft enduring in a remote jungle

location as a result of the natives rigorously enforcing local

taboos.

The story could

be a chapter from Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World

(1914).

More

prosaically?, less exotically? less romantically? , the padua

encapsulates James Hornell's theory of the development of

ancient water-craft - it is virtually a "missing-link."

In Water

Transport- Origins and Early Evolution (1946), Hornell

proposed that the first water-craft was the "swimming or

riding float" (hereafter, the float board), which facilitated

the development of swimming and was the basis for the next

technological advance, the raft.

He further

suggested that the float board itself continued to evolve,

reaching its highest level of sophistication as the Hawaiian

surfboard.

Lake Botsumtwi

is formed in the basin of of meteorite impact crater, 10.5 km

in diameter, and estimated to be 1.07 million years old.

While the

bottom of the lake has gradually risen with the deposition of

eroded sediment from the crater walls, its catchment is

limited to rain falling directly within the crater's rim.

As the climate

has fluctuated over millennia, the lake's size has varied

markedly, on occasion rising above the lowest points of the

rim and, at the other extreme, reducing to a small pond.

When Robert

Rattray visited the lake in 1921 there were 26 villages, but

he was told of another four that had recently been submerged

He confirmed

that had been an increase in the level of the lake, evidenced

by a number of surviving tree stumps.

This is well

illustrated in Rattaray's photographs, which are a valuable

adjunct to the text.

Recognised as

a special place of religious significance, severe limitations

were placed on the technology employed by the native fisherman

on Lake Botsumtwi, retaining a Neolithic culture despite far

more advanced technology being readily available.

A firmly

established religious belief, in practice it also probably

served, to some degree, to manage the fish stock.

Only swimming

and paddling on float boards, the padua, are permitted

on the lake.

When swimming,

they use "either the ordinary breast stroke or a double

overarm with a scissor-like kick of the legs," the latter

directly associated with an established familiarity of

propelling float boards.

The padua

are rough hewn from logs of a light wood, "almost as soft

as cork."

Rattray gives

the botanical name as Musanga Smithii, which has since

been reclassified as Musanga cecropioides.

This fast

growing, but short-lived, tree has a straight trunk, up to19

inches or 0.5 metre in diameter, and reaches heights of 60-150

feet or 18-45 metres.

It features an

umbrella-shaped crown and is dioecious, a feature

common to primitive species

Reported as

rare in the tropical jungle, forest swamps and along rivers,

it is not immediately apparent if the fisherman of Lake

Botsumtwi obtained this timber from the shores of the lake or

from outside the crater.

Unfortunately,

Rattray does not provide an account on where or how the

corkwood trees where harvested, or how the padua was

constructed.

Given the the religious significance of the lake, this may

have had associated ceremonies or incurred some restrictions,

such as the use of metal tools.

Note that the padua

builders, like many boa t-builders, construct

replicas of their craft, and a small model padua presented

to Rattray is shown in Fig. 13.

The padua are

6

in. to 8 in. thick, about a foot wide, range in length

from 6 to 10 feet, and the template is trimmed at the nose

and the tail.

As Dawson

notes, the padua resemble (some of) the

surfboards of ancient Hawaii.

In particular, there are a number of features similar to the olo-

a "thick" and "narrow" board that was 5 to 8 inches deep,

usually less than 15 inches wide, and made from light-weight willi

willi.

The olo was

reported

to be built up to extreme lengths for the surf riding chiefs,

reliably up to about 16 feet, and was ridden prone.

While its forte

was undoubtedly as a paddle board, its wave riding performance

was improved with its high dome deck and bevelled rails.

Like the padua,

the olo was likely to be cut from an individual tree

trunk, unlike the most common board in Polynesia, the alaia.

A wide and thin

board, the alaia was shaped from plank (or

billet) of koa, one of several previously split

in sections from a log.

Rattray's

photographs show a range of dimensions and design features;

some have a square box-rail and some have rocker, where the

"ends stood out of the water higher than the centre."

As with all

one-piece timber craft, some of these elements were probably

determined by qualities of the harvested tree.

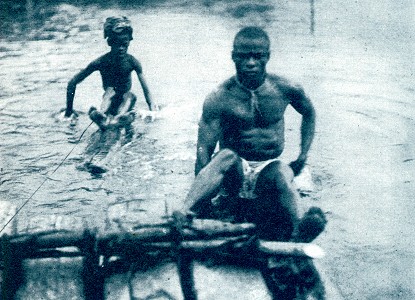

The padua

is propelled in the standard prone paddling manner,

Rattray noting that "perfect steering control is obtained by a

flick of the foot upon the surface of the water.'

IHe notes

that the padua is propelled along the surface of

the water much faster than an ordinary canoe is paddled or

poled by one man, " and Fig. 13 certainly shows two young

riders leaving a significant wake as they paddle away from the

camera.

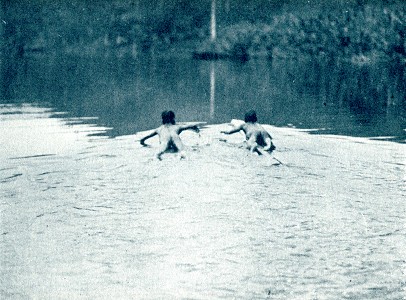

The photographs

in Fig. 9 and 10 show the padua riders astride their

boards with confidence and a relaxed demeanour, reminiscent of

photographs of groups of surfboard riders waiting for

set-waves outside of the surf zone.

R. S. Rattray identifies four simple types of nets used on the lake made from strips of a local reed, and an "even more" primitive method called abontuo, where the fisherman dives for fish on bottom, returning to the surface hands free and holding the catch with their teeth, page 66..

When goods or

passengers required transportation, several padua are

tied together to form a raft, a mpata.

As illustrated

in Figs. 13 and 14, the mpata is either shunted,

with the nose of the padua or the rider's foot held

against the stern, or towed with a line of creeper

usually tied around the rider's ankle, or a combination of

both.

Surfboard

riders would recognise the similarity of the tow-line to the

modern safety accessory, the leg-rope or leash.

If the padua

and the skills of their riders were transposed back in time to

the coast of West Africa, it may suggest how these simple

craft could fully provide the transport and fishing needs of

early coastal dwellers.

They would have

also been particularly effective in the surf zone and highly

suitable as surfboards.

In light of this study of the water-craft of the fishermen of Lake Botsumtwi, Hornell's thesis may be slightly refined.

The first

watercraft, the float board (padua) had an extended

period of use, which facilitated the development of swimming.

Long-term

familiarity with the float board presented the possibility of

a composite craft, the raft (mpata).

Initially, the

raft did not require the use of the pole for propulsion,

although this would surely have been quickly adopted in

shallow waters.

The dugout

canoe was a significantly later development, requiring a far

more sophisitcated technology, and which only became highly

effective in deep water with the development of the paddle, or

the bladed pole.

A simple paddle

was probably first used to propel small rafts, as exemplified

by the catamaran riders of Madras on the coast of

India, as were likely the first experiments with sails.

There are

currently about 30 villages in the vicinity of Lake Botsumtwi

with a combined population of about 70,000 people, placing

considerable stress on the local environment..

Largely now

noted as a tourist resort, the traditional fishing methods

using the padua are still in practice as of 2013.

References

1. James Hornell : Water Transport-

Origins and Early Evolution.

Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge,1946.

2. Dawson,

Kevin

: Swimming, Surfing and Underwater Diving in Early Modern

Atlantic Africa and the African Diaspora.

Carina Ray and

Jeremy Rich, eds., Navigating African Maritime History

Research in

Maritime History book series,

Memorial

University of Newfoundland Press, 2009, pages 81-116.

http://history.unlv.edu/faculty/dawson/Swimming

&

Surfing in Africa copy.pdf, viewed 10 April 2013.

Dawson notes on page 104:

"branch or

miscellaneous plank from a Western ship served the purpose.

Paddleboards

were buoyant enough to carry both their paddlers and small

cargoes.

Most likely

these boards were the prototype for Atlantic African

surfboards. (59)

While at

Elmina in the 1640s, Michael Hemmersam wrote that two canoemen

used a plank as an impromptu paddle-board.

When these

Africans went below Ambtsforth’s deck, 'their canoes drifted

away; so, without being at all afraid of drowning they laid

themselves on a board thrown out to them be the skipper and

swam ashore with it.

We were all

quite amazed at this great feat of daring.' (60)

When Robert

Rattray visited Lake Bosumtwi, he described and photographed

mpadua that probably closely resembled early Gold

Coast

surfboards.

“The ends of

some padua are cut away at both extremities so as to offer

less resistance than a blunt prow, and a few were seen in

which these

ends stood out of the water higher than the center,” wrote

Rattray.

Indeed, mpadua

are surprisingly similar to ancient Hawaiian surfboards and

even modern longboards. (61)

(Footnotes)

59. Finney,

'Surfboarding in West Africa,' 42; Jones (ed.),German Sources

103 and 109, and Hair, et al. (eds.), Barbot on Guinea, II,

532.

60. Quoted in

Jones (ed.),German Sources, 103.

61. Rattray,

Ashanti, 60-65. (page 104)"

These

references are:

Finney,

“Surfboarding in West Africa,”

Jones, ed., German Sources for West African History 1599-1699, Wiesbaden, 1983?

Paul Edward

Hedley Hair, Adam Jones, Robin Law (eds.):

Barbot on

Guinea:- the writings of Jean Barbot on West Africa

1678-1712, Hakluyt Society, 1992

Google

Books

http://books.google.com.au/books/about/Barbot_on_Guinea.html

Barbot reports

Page 532

[At ?,

circa 1712]

...

misfortune, with little or no concern, but this must proceed

from them being brought up, both men and women, from their

infancy, to swim like fishes; and that, with the constant

exercise, renders them so dexterous at it, tho' the canoo be

overturn'd or split to pieces they can either turn it up

again in the first case, [or] ...

... may be seen several hundred of boys and girls sporting together before the beach, and in many places amoung the rolling and breaking waves, learning to swim on bits of boards, or small bundles of rushes, fasten'd under their stomachs, which is a good diversion to the spectators. (50)

3.

Wikipedia: Lake Bosumtwi

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Bosumtwi,

viewed

11 May 2013.

"There is a

traditional taboo against touching the water (at Lake

Bosumtwi) with iron and modern boats are not considered

appropriate.

The padua, a

wooden plank requiring considerable skill to maneuver, is the

legitimate method.

4. Virtual

Tourist

http://cdn3.vtourist.com/4/3252021-Lake_Bosumtwi_Ghana.jpg

LAKE BOSOMTWE

I shall now

proceed to a more or less detailed account of this

lake, giving the results of investigations made on the

spot between the 1st and 14th of October 1921.

Bosomtwe is

a lake in Central Ashanti lying approximately in Lat. 60 30'

N., and Long. ro 25' E.

It is just

over five miles long and just under five miles broad.

It lies in a

perfect bowl.

Page 55

or cup, the

sides of which are thickly wooded hills rising about 500-700

feet above the lake, which I have been informed is itself

some 200 feet above sea level (vide Fig. I).

It has no

outlet, but there are many small streams flowing into it

from the mountain sides, and these, with the storm water

from the hill,slopes, form apparently its source, of supply.

Its general

appearance at once gives the layman the idea that its bed

was formerly the crater of a volcano.

The lake

shore is closely dotted with villages, of which there are

now twenty six.

There were

formerly thirty, but four have been submerged and not

rebuilt.

A fuller

account of these submerged villages will be given later.

The

previous sum total of our knowledge concerning this lake is,

I believe I am correct in stating, contained in an article

by Mr. Kitson, C.M.G., C.B.E., Goverment Geologist, a copy

of which is given in an appendix.

His short

geological report is most valuable and negatives the

phenomenon I shall describe presently being due to volcanic

causes.

Facing page 60

|

The making of the raft. |

|

The raft at the landing-place at Abrodwum. |

|

Showing various positions on mpadua. |

This

concludes alI I could discover concerning the myths,

traditions, and magic, religious aspect of the cult of this

lake,

which has-so

myth and tradition say-forbidden, and up to the present

forbidden with success, the use of any of the following

methods of catching fish, all equally 'hateful' to Twe, the

anthropomorphic lake god.

I. Iron

hooks of any description, or any kind of lure or line

fishing.

2. Asawu

(cast nets).

Page 62

3. Seine

nets.

4. The use

of canoes, boats, sails, paddles, poles, or any hollowing

out, even of a log.

5. Brass or

metal pans (only wooden ones must be used).

While the

following rules must also be observed:

6. No

fishing on Sunday. (1)

7. No

menstruating woman must go upon the lake.

Instead of

canoes, the lake-side dwellers go about on what each calls

his padua.

These are

logs with sides roughly hewn, as indicated in Figs. 6-9.

They are

made out of a very light wood almost as soft as cork called

odwuma fufuo, (2) and are anything from 6 ft. to 10

ft. long, about a foot wide, and 6 in. to 8 in. deep.

The ends of some padua are cut away at both extremities so as to offer less resistance than a blunt prow, and a few were seen in which these ends stood out of the water higher than the centre.

The

numerous photographs illustrating this chapter show more or

less clearly the different types.

Two or more

mpadua are lashed together to form an mpata,

or raft, and these are used to carry out the larger and

heavier nets to set up at the chosen fishing grounds.

Such a raft,

in process of construction and completed, is seen in Figs. 6

and 7.

No

cross-struts are placed underneath, those on top are

fastened by creepers, for rope may not be used, and such a

raft must only be propelled in the manner to be described

later.

It was upon

such a craft that my various expeditions upon the lake were

taken.

The

etymology of the word padua I have not been able to

trace with certainty.

Dua

is of course a log or a tree, and pa may be pa =

good; but if this be so we would expect the adjective to

follow the noun, and so have dua-pa.

Christaller

gives in his dictionary padua, a log or block of

wood in which the iron pa for securing the hand of a

prisoner is fixed, and also mpadua, a bedstead.

The latter

is possibly the same word, with the root mpa,

something to lie upon.

[Footnotes]

1. Even

should' the Lake explode its powder', on a Sunday no one

might touch the fish till Monday.

2. Corkwood

or Musanga Smithii.

For this and

other botanical names I am indebted to Major T. F. Chipp,

M.C., B.Sc., F.L.S., late Deputy Conservator of Forests,

Gold Coast, now Asst. Director at Kew.

Facing page 62

|

Showing various positions on mpadua. |

|

Villagers on mpadua turning out to meet our raft. |

Fig. 11. Two young scouts dashing off to announce our arrival. |

Fig. 12. On the lake: note the great tree top showing above the water. |

In spite of

the taboos forbidding the use of sail, paddle, oar, or pole,

the padua is propelled along the surface of the

water much faster than an ordinary canoe is paddled or poled

by one man.

The man on

the padua uses his hands as paddles, lying face down

on the log, when perfect steering control is obtained by a

flick of the foot upon the surface of the water.

The idiom

for to 'paddle' is yi abasa, lit. 'to =arm it '- 'to

throw out the arms '.

The various positions adopted on the padua will be understood from the photographs (Figs. 8-12).

The men are

very fine swimmers and some show magnificent muscular

development.

They swim

either the ordinary breast stroke or a double overarm with a

scissor-like kick of the legs.

My raft was pushed and drawn, and the endurance of the men was wonderful, for to swim while pushing a raft with two persons upon it for eight consecutive hours in a broiling sun is no small feat.

The 'pushers,' each on his own padua, kept the noses of their respective mpadua (or sometimes a foot) pressed against the stern of the raft, the' tractors' were in front lying flat on their mpadua with a piece of creeper tied round an ankle or sometimes simply held in the folds of the belly muscles, the other end being attached to the raft (see Figs. 13-14).

In Fig. 13

the small white object at the bow is a model padua

given me just before starting off, the rope is that used in

the sounding operation, to be described later.

This

photograph was taken about three miles from the north shore

on the return journey.

I did not

see any women on mpadua but was informed they were as expert

as the men, and this I quite believe, as I used to see whole

family parties alternately wading and swimming along the

lake shore instead of following the road running between the

villages.

Coming now

to the appliances used for fishing, these seem to be of four

kinds.

All are made

out of the same material, i. e. strips of the reed the

natives call sibire. (1)

All these

are really only slight variations of one simple design,

consisting of an oblong-shaped mat woven of simple

criss-cross pattern.

See

illustration on p. 64.

[Footnote]

1. A species of Clinogyne Scitamineae.

Facing page 64

Fig. 13. Showing method of propelling the raft: a tractor. |

Fig. 14. Propelling the raft from the stern. |

None of

these traps or nets, it will be noted, are self-acting, i.

e. apart from the fisherman there is nothing to prevent the

fish swimming into the net and swimming out again.

There is,

however, another way of catching fish which is even more

primitive.

It is called

abontuo.

The

fisherman dives under the water, remains under from thirty

to forty seconds, and comes up holding a fish between his

teeth - to leave the hands free for swimming.

I think they

catch these fish possibly lying on the mud at the bottom,

and' tickle' them just as boys do in Scotland in the burns.

All fishing

methods give, the fishers say, but poor and small results in

comparison with the tremendous hauls of fish sent by the

lake spirit when' Bosomtwe explodes his gunpowder '.

Page 74

"There is

only one real lake in the country, and that is the sacred

Lake Bosumtwi in central Ashanti, about 18 miles south-east

of Coomassie.

This

freshwater lake is roughly circular in shape, with a

diameter of about 4 miles and an area of some 13 square

miles.

It lies in a

deep depression, with steep sides rising to 600 and 700 feet

above its surface.

Its depth is

unknown.

An attempt

was made to sound it by Mr. A. J. Philbrick, acting Chief

Commissioner of Ashanti, but unfortunately when 500 feet of

line had been let down it broke, and the attempt was

abandoned.

Though a

lake with no outlet and only a few small annual streams

flowing into it, the wateris fresh.

Its general

appearance suggests a volcanic origin viz. that it is a

caldera, but since no evidence whatever has been found on

its north-eastern and northern rim and shore of young

volcanic rocks, that view is hardly tenable.

The

available evidence suggests its formation as due to

subsidence.

Numbers of

villages stand on the shores of the lake.

There are

several interesting native beliefs about the lake.

It is sacred

to the Ashantis, who regard it as a great fetish.

They believe

that it is the seat of a powerful and energetic spirit which

manifests itself intermittently on its open surface by

flashing lights making noises like the discharge of

artillery, and in various other ways.

No canoes,

paddles, fish-hooks, or brass pans are allowed on or near

it.

Fish abound

in the lake, and are caught in an ingenious manner by the

natives.

Plaited reed

mats with gaping mouths are taken out from the shore by men

lying face downwards on cigar-shaped logs of wood. They

propel themselves by paddling with their hands, and having

set and anchored the nets, mouths open, the lower platform

just submeIged, they retire for some time.

The fish

enter the trap and bask in the subdued sunlight, resting on

the lower portion.

The

fishermen return almost noiselessly, pull together the two

parts of the trap, capture the fish and tow them and the

trap ashore."

- Extract

from a paper read by Mr. A. E. Kitson, C.B.E. before the

R.G.S., June 1916.

Page 322

I have had

occasion several times in the preceding chapters to mention

neoliths, which in Ashanti are known as God's axes or God's

hoes, and the following fuller notes upon them may be of

interest.

In the year

1911 it was my good fortune to be in Ashanti during the

latter part of the construction of the Coo- massie-Ejura

main trunk road, and to have obtained a collection of celts

which were then unearthed.

These formed

the subject of a most interesting paper by Mr. Henry

Balfour- (of the Pitt- Rivers Museum, Oxford) in the

'Journal of the African Society, (1) and I advise all who

are interested to consult that article.

In 1921 I

found myself again in Ashanti as Government Anthropologist.

In the short

time that has elapsed since taking up my new work some

hundred more specimens of celts have been obtained, a few

being found by me in situ, and many were dug up by the

Ashanti farmers, and one, the largest, was lately dredged up

from the bottom of the Offin River.

Some were

associated with the cult of the abosom, the suman, or of ,

Nyame.

While it is

correct to state that probably ninety-nine out of a hundred

Ashanti declare and actually believe that the stone celts

found by them emanate from the sky, and are in consequence

endowed with some of the power of the Sky God, Nyame,

sufficient evidence is available to prove beyond a doubt

that there are still alive in Ashanti to-day persons who

know that these stones are artifacts, and that they were

used by their ancestors at a period that was relatively

recent.

The ~har.ti

generally call them' Nyame akuma or 'Nyame asoso, i. e. the

Sky-God's axes or hoes.

They believe

that they fall from the sky during thunderstorms and bury

themselves in the earth.

They think

that, as they come from' Nyame, they are endowed with some

of the power of that great spirit, and this is the

explanation of their use in connexion with abosom and of

their

[Footnote] 1. No. XLV. Vol. XII, October 1912.

Page 323

supposed

potency as medicine.

As a

consequence of this belief they are constantly to be found

as appurtenances to abosom (the gods), suman (charms),

'Nyame dua (altar to the Sky God), or placed in a pot where

the drinking water is kept, .to cool the heart '. They are

also sometimes fastened against the body to cure diseases,

or are ground down and the powder drunk.

.I am

inclined to believe it is thought heterodox to say anything

contrary to the above, because these, being the popular

beliefs, are encouraged by the akomfo (priests), and that

some of the old people who really know better say nothing,

confess ignorance, or acquiesce in the generally accepted

opinion.

Nevertheless, I have been informed by several old men that, according to traditions handed down to therI:l, the so-called .God's axes' were really tools used by their ancestors in the past, not only previously to but contemporaneously with, a period when the smelting of iron was practised.

Kakari, an

exceptionally intelligent Ashanti, gave me the following

statement, before I was aware of the existence of the very

long celts here illustrated:

.My

grandfather, Kakari Panyin, once told me that he had been

told by his grandfather, who himself had heard of, but had

not seen them in use, that very very long ago the Ashanti

used the stone hoes which are now called' Nyame akuma. My

grand- father also told me our ancestors formerly wore a

girdle with leaves before and behind. He said these axes

were not originally the short things now found but were very

long, and that they used them for hoeing, holding them in

both their hands and digging between their open legs'

(translation from the ver. nacular). Kakari could not say

clearly whether they were hafted or not. He picked up a

stick lying 'against the verandah, to show the length, and

held it about If to 2 feet up the shaft.! Later, and after I

had seen the long celts (Figs. 41 and 142), another old man,

Kobina WUSU,2 between seventy and eighty years of age, told

me that his grandfather once told him that very long ago the

Ashanti used hoes made of stone a cubit long, demonstrating

this by holding out the right arm, fingers pointing, and

touching the elbow-joint with the left hand. When asked

1 A celt of

this length, from the Gold Coast, is now in the British

Museum. 2 His photograph may be seen in Fig. No. 41.

Page 324

why they

did not use iron, he replied that they also used it but that

it was scarcer and more difficult to work than stone, and

was only used for making nabuo (iron money). These

statements were made independently, and neither informer had

ever had any intercourse with Europeans, and neither had

been told by me the real origin of these celts. The points

of interest in these statements are:

I. The fact

that a definite tradition still survives of a stone age.

II. The

statement in each case that the celts were long (a foot or

more).

III. The

fact that in one case iron-working was stat~d to have been

practised contemporaneously with the use of stone.

It may be

here noted that the late Major Tremeane, in Nigeria,

also once

met an old native who knew the true origin of these'

celts. I

shall have more to say later as to the length of the celts.

It may be stated, however, that long celts have been

discovered; for example, one numbered I in Fig. 141 measures

24 centimetres. Long celts were apparently already known;

Mr. Balfour, in the article alluded to, speaks of .two long

slender celts from the Offin River', but does not give their

dimensions.

With regard

to iron currency, I had not before heard of nabuo or of an

iron currency in Ashanti. Moreover, the Ashanti do not now

work iron ore, nor are there any obvious traces of their

ever having done so.

In Chapter

IV, p. 47, of a rather rare old book entitled History of the

Gold Coast and Ashanti,l by a native pastor, the Rev. C. C.

Reindorf, in referring to Kwabia Amanfi, one of the earliest

Kings of Ashanti of whom tradition has any record, writes:

.All we know of him is that in his days gold was not known,

the currency was pieces of iron.'

The word

nabuo, used by the old Ashanti, is without doubt derived

from two words, dade, with a plural nnade, iron ore, and

buo, to pound or break up, and it describes the process by

which the laterite found in Ashanti was prepared for

smelting.

Ashanti

traditional lore seems to go back to this first King Kwabia

Amanfi. Reindorf gives his date very roughly as 1600,

1 Printed at

Ba..,le.

Page 325

and fifteen

Ashanti kings are recorded since then, ending with Prempeh,

who was exiled in 1896.

We thus have

some approximate data which would appear to point to the

fact that four hundred to five hundred years ago iron was so

little worked-1 do not say known-that it was used as

currency in Ashanti. If this be so, then we should expect

-an

overlapping of the Stone Age with the Iron Age until Euro-

pean iron was imported, and further interesting evidence

seems to confirm this supposition.

Before

passing on to this I may state that in Reindorf's History,

he also constantly alludes to the lost art of iron-smelting

in Ashanti, which, according to him, vanished when iron rods

began to be imported from Europe. These rods were apparently

at first used a-" currency, for he talks of 'the piece of an

iron bar which was the ordinary pay of a soldier '. I have

never seen any of this nabuo or iron currency, and there are

not any visible traces in Ashanti of iron furnaces, such as

may be seen in Togo- land.l There is, however, evidence that

iron was once worked.2

The town of

Obuasi in Ashanti is the centre of a large gold- mining

industry; it lies in a valley surrounded by isolated hills

which rise to a height of 500-600 feet from the plain below.

Many of these hills have been cleared of the dense forest

which formerly grew upon them, and are now occupied by

Government bungalows. There is neither outward sign n.Ql"

tradition of these having been the settlements of the

Ashanti in the past, but to judge by the remains under the

soil, they must have been the former sites of large

communities.

It is no

exaggeration to state that there is hardly a square foot of

ground on the tops of some of these hills which does not

contain fragments of pottery; and I was informed many celts

had also been found there. The pottery bears an endless

variety of designs, herring bone, bands, elliptical

punch-marks, contiguous and detached circles, &c. A celt

was also found by me about 6 inches below the surface (Fig.

140, no. 3). A few yards from it and in the same strata were

unearthed two curious objects of clay, one apparently

unbaked, the other having been

1 See' The

Iron Workers of Akpafu'. J. R. A. I., Vol. XLVI. 1916, by

R. S.

Rattray.

2 Since my

return to Africa two manilla were brought to me, they had

been dug up near Lake Bosomtwe.

Page 326

subjected to

intense heat (Fig. 14°, nos. I, 2, and 4). These seemed to

be fragments of a pipe, and reconstructed would have

..t.:-

this

appearance:

For some

time I could not obtain any explanation

: of these

objects; later, novkver, on my showing the collection of

pottery to an old Ashanti, he singled out these fragments at

once and said they were nsemua (sing. semua). He stated he

recognized

them as similar to one he had at home which had been handed

down by his ancestors. The semua, so he had~een told, was

used for smelting gold. The one in his possession was sent

for and

later presented to me. It was completely glazed and

encrusted

with a dark brown substance (Fig. 140, no. 4). The nsemua

found by me, the pottery and a celt, were all discovered on

the east side of the hill known as D. C.'s hill, and about

ten yards from the flat top upon which the bungalow I was

then living in was built. An examination of these nsemua,

(two found by me and one given to me) made in the Assay

Office of the Ashanti Gold-fields Corporation, gave the

following result:

.Semua. Both

samples which have been used show only

a trace of

gold.'

, One end of

the unbroken semua is encrusted with a dark brown substance

which corresponds to Ferrous Silicate.'

.This

material is only present at one end, the other end being

quite free.' ..

.An unused

semua shows on grinding that it is composed of unburnt clay

and sand intimately mixed.'

, There is

no room for doubt that the semua were tuyers used

in a native

blast furnace and that one specimen was that end which came

in contact with the molten slag.'

Mr.

Mervyn-Smith, the Acting Manager of the Ashanti Gold- fields

Corporation to whose courtesy and interest I am in- debted

for the assay of these specimens, also sent me a paper by J.

Morrow Campbell-read before a meeting of the Institute

NEOL~THIC

IMPLEMENTS IN ASHANTI 327

of Mining

and Metallurgy I-from which the following is an extract:

, In various

parts of the Gold Coast from the shores of the

N ani lagoon

to Ashanti are to be seen heaps of slag. No remains of

furnaces are to be found. ...

.They are

generally attributed to the Portuguese, but this is not

credible.'

Mr. Campbell

then proceeds to describe native blast furnaces in Haute

Guinee j he writes:

'. ..when

the walls have reached a height of 18 in., about

a dozen

irregular elliptical holes about I ft. long by over 6 in.

high are left at equal intervals. A large number of open

pipes or ,. Tuyers ", tapering from about 2 in. at one end

to over I in. at the other and over 1 in. in thickness,

composed of a mixture of clay an1i sand, are made and

thoroughly dried in the sun. They are inserted small end

downwards,' &c.

I think

enough has been said to indicate that those nsemua found

associated with a celt, are relics of an iron-smelting age

in Ashanti, and would seem to show that the Stone Age in

Ashanti survived into comparatively recent times and over-

lapped the Iron Age.

With

reference to the statements of those Ashanti, who say that

the stone hoes or axes were originally longer than those now

commo~ly known, I propose to consider some specimens I have

at present available, with a view to seeing if this is a

reasonable supposition. An examination of any collection of

West African celts-I have about a hundred before me as I

write, not including the photographs of forty-one more in

the article by Mr. Balfour, to which reference has been

made-will show that they fall into one or other of the

following groups (see p. 328).

I. Short

celts with ground edges and tapering butt (A).

2. Short

celts with ground edges, the butt as wide, or nearly so, as

the cutting edge (B).

3. Short

celts in all stages intermediate between these two.

4.

Cylindrical stones with both ends blunt (no cutting-edge)

(c). 5. Cones (D).

6. Very long

celts tapering towards the butt (rare) (E) (see p. 329). Let

us now take any of the longer celts shown in Fig. 141,

1 No. 67.

4th April 1910.

|

Ashanti Negro Universities Press, New York,1969.. [cropped] |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |