surfresearch.com.au

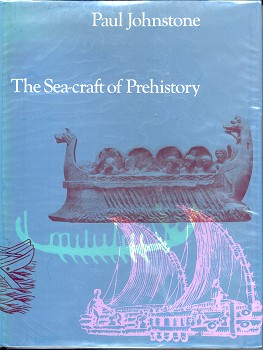

johnstone : sea-craft

prehistory, 1980

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

surfresearch.com.au

johnstone : sea-craft

prehistory, 1980

|

|

Prepared for publication by Sean McGrail. Routledge and Keegan Paul Ltd., London, 1980. |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |