surfresearch.com.au

george marvin : the surf at waikiki, 1914.

george marvin : the surf at waikiki, 1914.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

surfresearch.com.au

george marvin : the surf at waikiki, 1914. |

| Page 24 THE SURF AT WAIKIKI

By GEORGE MARVIN Illustrated with Photographs EVERY country has its own customs in sport as in other things. It has remained for Hawaii to reign preeminent in the manly sport of surf-riding. The conformation of the beach and the bottom along the island shores brings the waves in in long, carrying swells that shoot the expert rider toward shore with the speed of an express train. None but a strong swimmer dare venture out, but for those who can do the trick there is nothing can beat the sensation. The article which follows is a narrative of a typical experience at Waikiki, where the conditions are perhaps the best in all the islands, as recounted by a newcomer. |

ONE OF

THOSE OUTRIGGER CANOES, WITH TWO HUSKY

KANAKAS PADDLING IT, BELONGS TO LINDA, THE DILATORY, WHO IS KEEPING US WAITING RIDING THE SURF AT WAIKIKI |

|

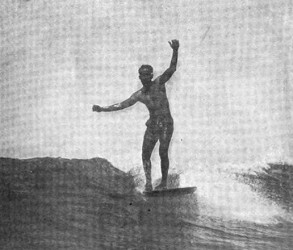

PICK A STEEP SURF WITH A JAGGED, DANCING EDGE AGAINST THE SKY |

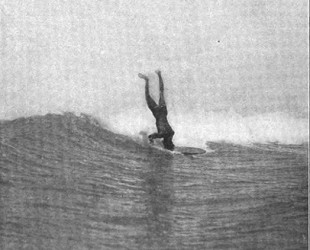

HIS LEGS IN

THE AIR

LIKE THE SPARS OF A DERELICT |

|

|

FLAT ON HIS

CHEST, HIS LEGS CHURNING THE WATER

BEHIND IN THE TRUDGEON STROKE, HE KEEPS HIS ARMS GOING LIKE PADDLE-WHEELS EACH SIDE. |

|

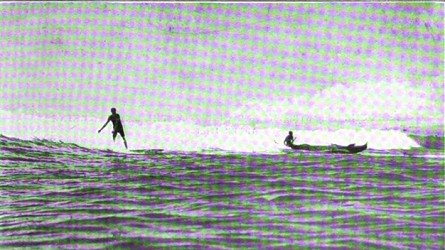

SURFER AND

CANOE FINISHING TOGETHER WELL DOWN

AT THE BASE OF A NEARLY SPENT WAVE |

THE DUKE GOES STREAMING BY, LIGHT AS THE SPRAY SMOKING AFTER HIM |

|

|

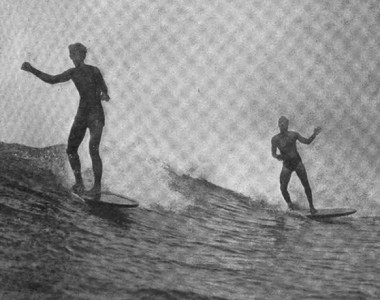

TWO YOUTHFUL

TRITONS SHOOTING DOWN AT US

|

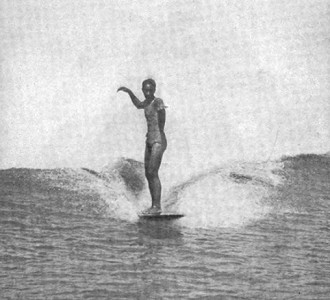

A KAMAAINA (OLD-TIMER) BALANCING ON ONE LEG AT THIRTY-FIVE MILES AN HOUR |

|

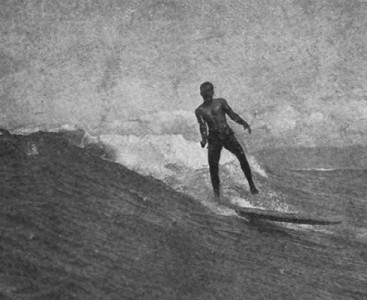

THE SURFER

HAS JUST RISEN ERECT AT THE MOMENT OF BREAKING

THROUGH THE TOP OF THE WAVE

|

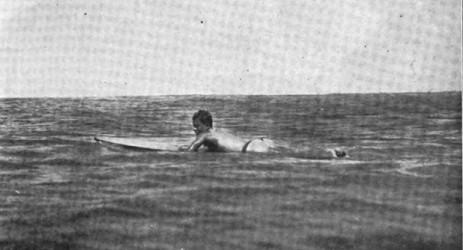

A BROWN

MERMAN, STRETCHED OUT HALF SUBMERGED ON HIS

LIGHT SHINGLE, WAITING FOR THE RIGHT WAVE TO

ARRIVE

|

|

A DULL, HEAVY-MOVING WAVE WITH A LUMPY SURFACE. LET THIS KIND GO BY |

|

RISE HEAD AND BACK TOGETHER, FEEL FOR THE BALANCE CENTER, THEN STAND ERECT |

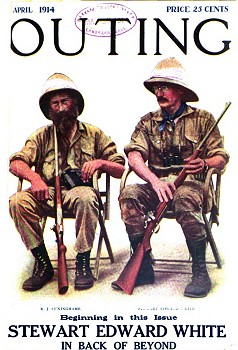

Outing. Outing Publishing Company, New York, Chicago Volume 64 Number1 April 1914. Hathi Trust https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hxj1mj |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|