surfresearch.com.au

Jacob Bronowski:

The Ascent of Man: 2, 1973.

|

surfresearch.com.au

Jacob Bronowski: The Ascent of Man: 2, 1973. |

| Chapter 1: Lower than the Angels |

Chapter

3: The

Grain in the Stone

|

| The pace of cultural evolution | Nomads: the Bakhtiari | 1st agriculture: wheat | Jericho - Earthquake

Land |

| VillageTechnology: The wheel | Domesticated Animals: the horse | War games: Buz Kashi | Settled civilisation |

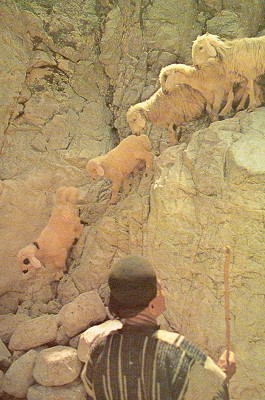

The first wife of Bakhtyar had seven sons, fathers of the seven brother lines of our people.As with the children of lsrael, the flocks were all-important; they are not out of the mind of the storyteller (or the marriage counsellor) for a moment.

His second wife had four sons.

And our sons shall take for wives the daughters from their father's brothers' tents, lest the flocks and tents be dispersed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

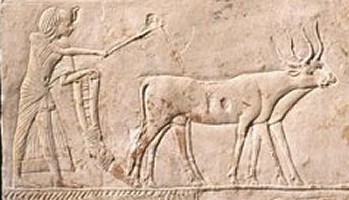

27. Give me a lever and I will feed the earth. Ploughing with harnessed oxen, Egypt. [Pages 74-75] |

|

|

28. The

wheel and the axle are the double-root from

a. Copper model of a war

chariot, Mesopotamia, c. 2800BC.which invention grows. b.

Roman mosaic of a solid wheeled cart.

[Page 76] |

|

a.

Mongol cavalry

|

30. The

mobile hordes transformed the organisation of

battle.

Right:

from

the Jami' al-Tawarikh,

|

| For the rider visibly is more

than a man: he is head-high above others, and he

moves with bewildering power so that he bestrides

the living world. When the plants and the animals of the village had been tamed for human use, mounting the horse was a more than human gesture, the symbolic act of dominance over the total creation. We know that this is so from the awe and fear that the horse created again in historical times, when the mounted Spaniards overwhelmed the armies of Peru (who had never seen a horse) in 1532. So, long before, the Scythians were a terror that swept over the countries that did not know the technique of riding. The Greeks when they saw the Scythian riders believed the horse and the rider to be one; that is how they invented the legend of the centaur. 31. Greek vase

painting, c.6o BC. Centaurs

and a warrior arming.

[Page 83]

|

|

|

Chapter 1: Lower

than the Angels

|

Top |

Chapter

3: The Grain

in the Stone

|

| 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. |

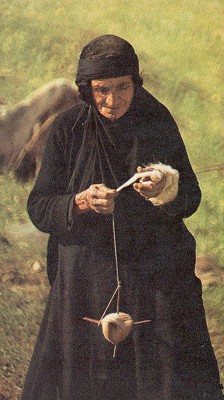

Bakhtiari

Spring Migration (Anthony Howarth for Daily

Telegraph Colour Library) p58. Bakhtiari Spring Migration (Anthony Howarth for Daily Telegraph Colour Library) p62-p63 Curved sickle, Ashmolean Museum p65. Neolithic Sickel [Neolithische Sichel] (Museum Quintana, Wolfgang Sauber) (wikipedia) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sickle#/media/File:Museum_Quintana_-_Neolithische_Sichel.jpg Old and new strains of wheat (Tony Evans, Marcel Sire) p66, p67. Wild wheat, from Jaubert and Spach, Oriental Plants (British Museum, Natural History) p68-p69. Objects from the Jericho site: a. Mud-dried brick, British Museum; http://www.handmadebrick.com/blog_direct_link.cfm/blog_id/62158 b. Quartzite lovers, Ashmolean Museum; [British Museum] c. Plaster-decorated skull, Ashmolean Museum p70-p71. http://www.realhistoryww.com/world_history/ancient/Canaan_1.htm d. The tower at Jericho tel (Dave Brinicombe) p71. The tower at Jericho tel https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jericho#/media/File:Tower_of_Jericho.jpg a. Carpenter, National Museum, Copenhagen; p72. Denmark, Copenhagen, Nationalmuseet (National Museum, Art Museum), Greek Civilization, Classical Age (450-323 B.C.) http://www.gettyimages.com.au/detail/photo/greek-fictile-figurine-of-carpenter-at-work-high-res-stock-photography/102520113 b. Clay treaty nail, British Museum, London, p72. Clay Nails - Louvre - AO22934 & AO12480.jpg (wikipedia commons) - the oldest diplomatic document known, found in Telloh, ancient Girsu, ca. 2400 BC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Clay_Nails_-_Louvre_-_AO22934_%26_AO12480.jpgoldid=80799262 c. Baker's oven, British Museum, London, p72, d. Greek toy, British Museum, London, p73. e. Old man with a wine press, British Museum, London, p73. Satyr working at a wine press of wicker-work mats, 1st century AD relief. (wikipedia) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_wine Ploughing with harnessed oxen, Museo Civico, Bologna (C. M. Dixon) p74-p75. The relief with a scene of work in the fields, Archaeological Museum of Bologna. http://www.museibologna.it/archeologicoen/percorsi/66287/id/75337/oggetto/75338/ a. Copper model of a war chariot, Baghdad Museum (Oriental Institute, University of Chicago) p76 Copper model of a quadriga from Shara Temple at Tell Agrab, Iraq, c. 2600 BC. Oriental Institute of Chicago. https://traveltoeat.com/chariots-the-first-wheels-of-war/ b. Roman mosaic of a solid wheeled cart, Royal villa, Casale (C. M. Dixon) p76. http://in-sicily.blogspot.com.au/2014/05/mosaics-in-villa-romana-del-casale.html a. Carpenters at work with a bow-lathe (India Office Library) p78. b. A mid-nineteenth 'hakak' polishing hardstones on a bow lathe. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/w/shah-jahans-jade-cup/ a. Mongol cavalry, and [b] troops fording a river, from the Jami' al-Tawarikh (Edinburgh University Library) p81. c. Mongol cavalry (?) http://www.hexapolis.com/2014/10/09/14-intriguing-things-you-may-not-have-known-about-the-mongols/ Greek vase painting, British Museum, London (Roynon Raikes) p83. Buz Kashi, Afghanistan (David Stock) p84-p85. a. Game of buzkashi in Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan, Dec. 18, 2001. (wikipedia) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buzkashi a. Dedication to Oljeitu in a MS of the Koran, British Museum, London p86. a. Juz’ (section) from a Qur’an. Written for the Il-Khanid sultan Öljeitü, Mosul, 1310. (The British Library Board) http://www.bl.uk/ b. The tomb of Oljeitu Khan (Dave Brinicombe) p87. |

|

|

|

Chapter 1: Lower

than the Angels

|

Top |

Chapter

3: The Grain

in the Stone

|

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |