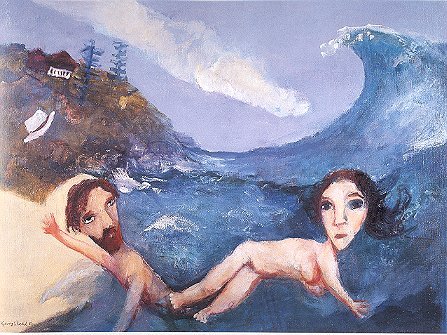

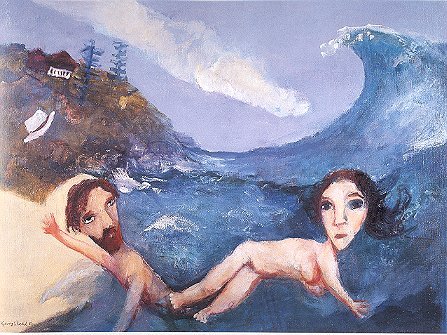

Garry

Shead:

The

Wave (1992)

Also see:

Appendix : the

wave in art

|

Shead, Garry (1942- ) :

The

Wave (1992)

Oil

on canvas board, 91 x121 cm

Private

collection.

From The

D.H. Lawrence Paintings, a series of

works based on D.H. Lawrence's Australian novel Kangaroo

(1923) and his time writing the novel at

Thirroul, NSW.

Lawrence,

his wife Frieda, the cottage Wyewurk, the

Norfolk pines and the rugged

coastline feature in most of the series.

One of the other thematic symbols of the series, a

large kangaroo, is absent from this work.

The

Lawrence works were initially encouraged by

Shead's contemporary, Brett Whitely, and in 1973

they produced a diptych Portrait of D.H.

Lawrence, see Grishin, page 51.

Brett Whitley (see above) committed suicide at

Thirroul in 1992.

The

wave image is reminiscent of Hokusai's Under

the Wave (1825).

Grishin, Sasha : Gary Shead and

the Erotic Muse

Fine

Art Publishing, St Leonards, Sydney. 2001.

|

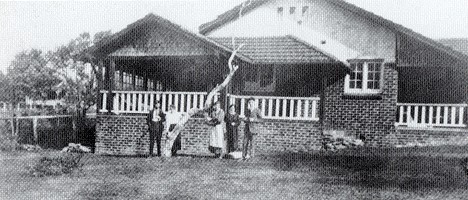

Lawrences and friends,

Wywurk, 1922.

(page 150)

Lawrences and friends,

Wywurk, 1922.

(page 150)